Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: Baudelaire on Fashion

Part 3: Tissot's Paintings

Tissot was intimately connected with fashion. One writer remarked, “At present time in England, Mr. James Tissot and Mr. George du Maurier exercise considerable control over the fashions.” Another wrote that Tissot “seems to have devoted himself chiefly to recording the fleeting fashions and affectations of modern costume, sometimes choosing for this purpose the most bizarre and the most hideous… the heads are quite subordinate to the turbulent mass of millinery which occupies the principle part of the canvas."

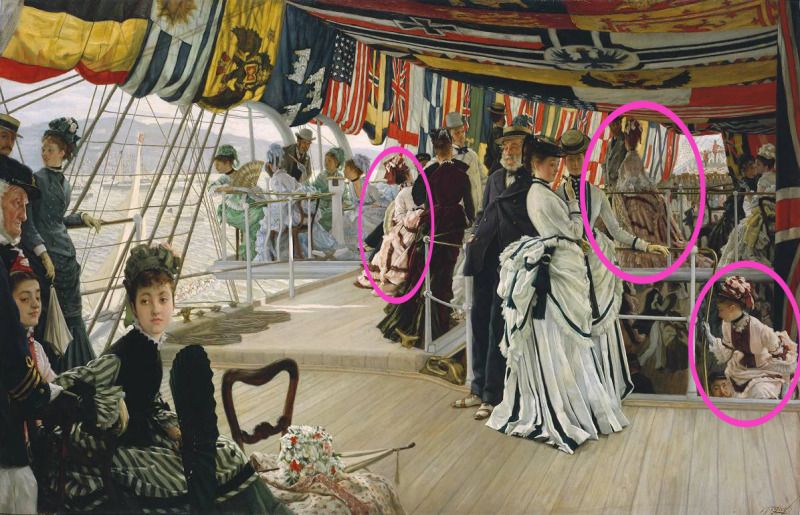

One of the most curious aspects of the three works I'm analyzing is the repetition of dresses, both within each painting and within the group as a whole. The woman who dominates the center of the canvas in Too Early wears a light salmon-pink dress with burgundy trim, the skirt falling in endless layers of ruffles. In the same work, a woman can be seen ascending the stairs, the coloring of dress and trim suggesting the same garment. The same dress is also worn by the woman sitting closest to the violinist in Hush!. The layers of ruffles and burgundy trim are also on a snippet of garment viewable at the edge of the canvas. The same dress is seen three times in The Ball on Shipboard, worn by a woman climbing the stairs, a seated woman, and a woman walking with a gentleman.

The Ball on Shipboard presents the most obvious set of duplicates. The two women standing by the railing wear identical dresses of white with black trim. In a group seated in the back corner, two women wear identical green dresses while another two wear low cut light blue dresses. These light blue dresses also look very similar to the gown worn by the subject of The Bunch of Lilacs (1875), and the two central figures in In the Conservatory (The Rivals) (The pink and burgundy dress also makes another appearance in this work).

Several explanations have been suggested for this repetition. Sometimes twins or sisters dressed alike. The repetition may have been derived from the multiple views of a single dress shown in fashion plates of the period. It may suggest the social faux pas of multiple women wearing the same dress at a social event. Or it may suggest a passage of time, with a single woman moving to different parts of the canvas. One of the most popular explanations is that Tissot had a limited number of actual dresses which he used as studio props, and so he simply repeated them in his various paintings.

However, the most compelling argument is that this repetition is a commentary on society and a reflection of Baudelaire’s modernity. Nancy Rose Marshall argues that “this sort of repetition suggested that ‘Woman’ in 1870s society was little more than a mass-produced commodity.” With the popularity of the department store and the rise of the ready-to-wear clothing industry, fashion was becoming more homogenized and democratized. Class lines were no longer easily distinguishable through dress. Women could purchase garments which were fashionable, but mass produced. While in previous centuries luxury was relegated to the few, increasingly in the nineteenth century luxury—or at least an appearance of luxury—could be gained by the many. As noted by Baudelaire, a womans dress was connected with her very being, thus indicating that a woman in a mass produced dress is a mass produced figure herself. This idea is reflected in the fashion in Tissot’s art, the repetition of clothing creating duplicates. The women are literally mass produced. Continuing in this line of reasoning, the women then become commodities, just like the clothing they wear. Their fashion sells the woman. As one commentator wrote, “The reason for the present extraordinary luxury in dress is that the surplus million of women are husband-hunting and resort to extra attractions to that end.” In the case of the women in Too Early, The Ball on Shipboard, and Hush!, the ostentation of their dress suggests that what they are promoting is their wealth and new status in society.

Tissot’s paintings emphasize the artificiality of society through the artificiality of fashion. As one writer wrote in 1867, it was an “age of shams”. He continues, saying “unreality creeps into everything… the consequence is that woman has become an imposture and men have learned to fear that what they most admire may be but a successful art.” With the elaborate construction of fashion in the early 1870s, women had literally become scaffolding on which to display ideas of wealth and beauty. Yet for the nouveau riche, this was a false portrayal, masking the reality of a newly emerging upper class which did not fully understand the rules of society. This was the reality of modernity, or at least the perceived reality of social commentators.

Selected Bibliography

Ash, Russell. James Tissot. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1992.

Baudelaire, Charles. The Painter of Modern Life. Translated by Jonathan Mayne. London: Phaidon Press, 1986.

Garb, Tamar. Bodies of Modernity: Figure and Flesh in Fin-de-Siecle France. New York: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1998.

Hollander, Anne. Fabric of Vision: Dress and Drapery in Painting. London: National Gallery Company Limited, 2002.

Marshall, Nancy Rose. “’Transcripts of Modern Life’: The London Paintings of James Tissot 1871-1882.” PhD diss., Yale University, 1997.

Marshall, Nancy Rose and Malcolm Warner. James Tissot: Victorian Life/Modern Love. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999.

Perrot, Philippe. Fashioning the Bourgeoisie: A History of Clothing in the Nineteenth Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Simon, Marie. Fashion in Art: The Second Empire and Impressionism. London: Zwemmer, 1995.

Wood, Christopher. Tissot. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1986.

Part 2: Baudelaire on Fashion

Part 3: Tissot's Paintings

Tissot was intimately connected with fashion. One writer remarked, “At present time in England, Mr. James Tissot and Mr. George du Maurier exercise considerable control over the fashions.” Another wrote that Tissot “seems to have devoted himself chiefly to recording the fleeting fashions and affectations of modern costume, sometimes choosing for this purpose the most bizarre and the most hideous… the heads are quite subordinate to the turbulent mass of millinery which occupies the principle part of the canvas."

|

| James Tissot. Too Early. 1873. Oil on canvas. London: Guildhall Art Gallery |

|

| James Tissot. Hush! 1875. Oil on canvas. Manchester: City of Manchester Art Galleries. |

|

| James Tissot. The Ball on Shipboard. 1874. Oil on canvas. London: Tate Gallery. |

One of the most curious aspects of the three works I'm analyzing is the repetition of dresses, both within each painting and within the group as a whole. The woman who dominates the center of the canvas in Too Early wears a light salmon-pink dress with burgundy trim, the skirt falling in endless layers of ruffles. In the same work, a woman can be seen ascending the stairs, the coloring of dress and trim suggesting the same garment. The same dress is also worn by the woman sitting closest to the violinist in Hush!. The layers of ruffles and burgundy trim are also on a snippet of garment viewable at the edge of the canvas. The same dress is seen three times in The Ball on Shipboard, worn by a woman climbing the stairs, a seated woman, and a woman walking with a gentleman.

|

| James Tissot. The Ball on Shipboard. 1874. Oil on canvas. London: Tate Gallery. |

The Ball on Shipboard presents the most obvious set of duplicates. The two women standing by the railing wear identical dresses of white with black trim. In a group seated in the back corner, two women wear identical green dresses while another two wear low cut light blue dresses. These light blue dresses also look very similar to the gown worn by the subject of The Bunch of Lilacs (1875), and the two central figures in In the Conservatory (The Rivals) (The pink and burgundy dress also makes another appearance in this work).

Several explanations have been suggested for this repetition. Sometimes twins or sisters dressed alike. The repetition may have been derived from the multiple views of a single dress shown in fashion plates of the period. It may suggest the social faux pas of multiple women wearing the same dress at a social event. Or it may suggest a passage of time, with a single woman moving to different parts of the canvas. One of the most popular explanations is that Tissot had a limited number of actual dresses which he used as studio props, and so he simply repeated them in his various paintings.

However, the most compelling argument is that this repetition is a commentary on society and a reflection of Baudelaire’s modernity. Nancy Rose Marshall argues that “this sort of repetition suggested that ‘Woman’ in 1870s society was little more than a mass-produced commodity.” With the popularity of the department store and the rise of the ready-to-wear clothing industry, fashion was becoming more homogenized and democratized. Class lines were no longer easily distinguishable through dress. Women could purchase garments which were fashionable, but mass produced. While in previous centuries luxury was relegated to the few, increasingly in the nineteenth century luxury—or at least an appearance of luxury—could be gained by the many. As noted by Baudelaire, a womans dress was connected with her very being, thus indicating that a woman in a mass produced dress is a mass produced figure herself. This idea is reflected in the fashion in Tissot’s art, the repetition of clothing creating duplicates. The women are literally mass produced. Continuing in this line of reasoning, the women then become commodities, just like the clothing they wear. Their fashion sells the woman. As one commentator wrote, “The reason for the present extraordinary luxury in dress is that the surplus million of women are husband-hunting and resort to extra attractions to that end.” In the case of the women in Too Early, The Ball on Shipboard, and Hush!, the ostentation of their dress suggests that what they are promoting is their wealth and new status in society.

Tissot’s paintings emphasize the artificiality of society through the artificiality of fashion. As one writer wrote in 1867, it was an “age of shams”. He continues, saying “unreality creeps into everything… the consequence is that woman has become an imposture and men have learned to fear that what they most admire may be but a successful art.” With the elaborate construction of fashion in the early 1870s, women had literally become scaffolding on which to display ideas of wealth and beauty. Yet for the nouveau riche, this was a false portrayal, masking the reality of a newly emerging upper class which did not fully understand the rules of society. This was the reality of modernity, or at least the perceived reality of social commentators.

Ash, Russell. James Tissot. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1992.

Baudelaire, Charles. The Painter of Modern Life. Translated by Jonathan Mayne. London: Phaidon Press, 1986.

Garb, Tamar. Bodies of Modernity: Figure and Flesh in Fin-de-Siecle France. New York: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1998.

Hollander, Anne. Fabric of Vision: Dress and Drapery in Painting. London: National Gallery Company Limited, 2002.

Marshall, Nancy Rose. “’Transcripts of Modern Life’: The London Paintings of James Tissot 1871-1882.” PhD diss., Yale University, 1997.

Marshall, Nancy Rose and Malcolm Warner. James Tissot: Victorian Life/Modern Love. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999.

Perrot, Philippe. Fashioning the Bourgeoisie: A History of Clothing in the Nineteenth Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Simon, Marie. Fashion in Art: The Second Empire and Impressionism. London: Zwemmer, 1995.

Wood, Christopher. Tissot. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1986.