Another month, another series of posts to give an in depth look at a particular fashion idea. This time, I'll be using Baudelaireian theory to analyze three paintings by James Tissot from the early 1870s. I hope you enjoy it!

In his seminal essay on painting and modernity, Charles Baudelaire wrote of the modern painter: “The crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water of fishes. His passion and his profession are to become one flesh with the crowd.” James Tissot embodied this sense of modernity. His paintings of contemporary life read as snapshots into the lives of the upper classes in the late nineteenth century. In particular, three works, Too Early, The Ball on Shipboard, and Hush!, painted in the early 1870s while Tissot was living in London, give a particularly fertile glance into society. These snippets of bourgeois society demonstrate, as Baudelaire wrote, the “fugitive, fleeting beauty of present-day life, the distinguishing character of that quality… we have colled ‘modernity.’” In his essay, Baudelaire emphasizes fashion as a crucial component to modernity. Contemporary fashion is intimately connected to contemporary life, thus giving a living humanity to a painting. Most importantly, fashion is connected with women. Baudelaire writes that contemporary fashion is a part of a womans being, an element which cannot be separated. In his three paintings from the early 1870s, Tissot explores these ideas of modernity and the identity of fashion.

Jacques-Joseph Tissot was born on October 15, 1836 in Nantes, France. His father, Marcel-Theodore, was a linen draper and his mother, Marie Durand, was a milliner, exposing Tissot to the world of fashion from his earliest years. He attended the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, where he befriended men such as James Whistler and Edgar Degas. However, the man who would have the most influence on his early career was Baron Hendryk Leys, who painted detailed scenes set in Northern Europe in the sixteenth century. Tissot admired the high degree of finish and real human interactions portrayed in Leys’ work. Tissot’s work was first exhibited in 1859, and to keep in line with a recent trend of anglophilia, Anglicized his first name to James. Through the early 1860s, Tissot displayed several ‘costume pieces’, set in previous centuries. In the mid 1860s Tissot broke from his historic style, keeping the focus on human emotions and interactions and a sumptuous materialism, but setting his pieces in the present day. With this work, Tissot finally began to achieve critical success.

In 1871, after the disastrous Franco-Prussian War, Tissot moved to London. He achieved great success, becoming a well-known public figure. In addition to full size paintings, he contributed several caricatures to newly launched Vanity Fair, a publication run by Tissot’s friend Thomas Gibson Bowles. In these sketches Tissot makes gentle mockery of public figures of the day, a theme repeated in his London paintings, which can be seen as a caricature of modern society. In 1876, Tissot met Kathleen Newton, a young divorcee. The two fell in love and began an affair. While many artists of the day had mistresses, few actually lived with them and non painted them with the frequency with which Tissot painted Newton. They lived together until 1882, when Newton died. Emotionally devastated, Tissot left London and returned to Paris. Increasingly interested in spiritualism and religion, Tissot’s art took a religious turn in the mid 1880s. His works on religious subjects were highly admired, once again earning Tissot fame and fortune. In the final years of his life, Tissot became increasingly recluse. He died on August 8, 1902 at Buillon, a private estate inherited from his father.

In his seminal essay on painting and modernity, Charles Baudelaire wrote of the modern painter: “The crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water of fishes. His passion and his profession are to become one flesh with the crowd.” James Tissot embodied this sense of modernity. His paintings of contemporary life read as snapshots into the lives of the upper classes in the late nineteenth century. In particular, three works, Too Early, The Ball on Shipboard, and Hush!, painted in the early 1870s while Tissot was living in London, give a particularly fertile glance into society. These snippets of bourgeois society demonstrate, as Baudelaire wrote, the “fugitive, fleeting beauty of present-day life, the distinguishing character of that quality… we have colled ‘modernity.’” In his essay, Baudelaire emphasizes fashion as a crucial component to modernity. Contemporary fashion is intimately connected to contemporary life, thus giving a living humanity to a painting. Most importantly, fashion is connected with women. Baudelaire writes that contemporary fashion is a part of a womans being, an element which cannot be separated. In his three paintings from the early 1870s, Tissot explores these ideas of modernity and the identity of fashion.

|

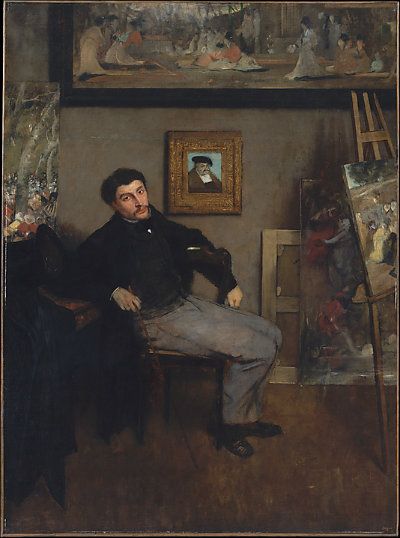

| James Tissot painted by Edgar Degas c. 1867-68. In the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

Jacques-Joseph Tissot was born on October 15, 1836 in Nantes, France. His father, Marcel-Theodore, was a linen draper and his mother, Marie Durand, was a milliner, exposing Tissot to the world of fashion from his earliest years. He attended the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, where he befriended men such as James Whistler and Edgar Degas. However, the man who would have the most influence on his early career was Baron Hendryk Leys, who painted detailed scenes set in Northern Europe in the sixteenth century. Tissot admired the high degree of finish and real human interactions portrayed in Leys’ work. Tissot’s work was first exhibited in 1859, and to keep in line with a recent trend of anglophilia, Anglicized his first name to James. Through the early 1860s, Tissot displayed several ‘costume pieces’, set in previous centuries. In the mid 1860s Tissot broke from his historic style, keeping the focus on human emotions and interactions and a sumptuous materialism, but setting his pieces in the present day. With this work, Tissot finally began to achieve critical success.

In 1871, after the disastrous Franco-Prussian War, Tissot moved to London. He achieved great success, becoming a well-known public figure. In addition to full size paintings, he contributed several caricatures to newly launched Vanity Fair, a publication run by Tissot’s friend Thomas Gibson Bowles. In these sketches Tissot makes gentle mockery of public figures of the day, a theme repeated in his London paintings, which can be seen as a caricature of modern society. In 1876, Tissot met Kathleen Newton, a young divorcee. The two fell in love and began an affair. While many artists of the day had mistresses, few actually lived with them and non painted them with the frequency with which Tissot painted Newton. They lived together until 1882, when Newton died. Emotionally devastated, Tissot left London and returned to Paris. Increasingly interested in spiritualism and religion, Tissot’s art took a religious turn in the mid 1880s. His works on religious subjects were highly admired, once again earning Tissot fame and fortune. In the final years of his life, Tissot became increasingly recluse. He died on August 8, 1902 at Buillon, a private estate inherited from his father.