Fabulous Fashionistas: Princess Pauline Metternich

10:54 AM

I first encountered Pauline Metternich when I was given an assignment in my 19th Century Fashion class last semester to pick a painting at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and write about it. My eye was caught, surprisingly enough, by a tiny impressionistic painting in the corner of one of the 19th Century European Art galleries. Little did I know that I was about to meet a woman who would become one of my favorite historic figures! I'll write more about her, because a short post couldn't possibly do her justice. If you would like to know more about Pauline, I highly recommend her memoirs, My Years in Paris. Until then, here's a little intro to Fabulous 19th Century Fashioista, Pauline Metternich! (I copied this post from the beginning of my paper, so you get some footnotes!)

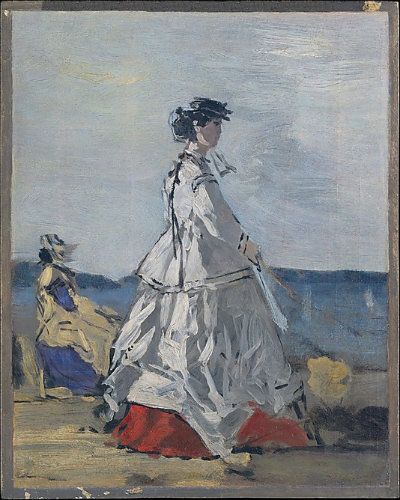

Eugene Boudin, Princess Pauline Metternich on the Beach,

c. 1865-67. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Pauline

Metternich (1836-1921)

was born to in Vienna to Count Mortiz Sandor, a Hungarian nobleman,

and Leontine von Metternich. Count Sandor was a famous horseman and, according

to his daughter, “daring to the point of recklessness, and altogether what is

best described as a ‘character’”.[1]

She married Prince Richard von Metternich, a diplomat, in 1856. In 1859, Prince

Metternich was “sent to France… in order to ratify some clause of the Treaty of

Zurich, which had been concluded when the war with Italy came to an end”,[2]

where his wife joined him. Prince Metternich was soon appointed Ambassador to

France, and the couple remained a fixture at the court of Napoleon III until

1870, when the Second Empire came crashing down.

Princess

Metternich had a strong personality. In the preface to her memoirs, The Days That Are No More: Some

Reminiscences (1921), Edward Legge writes that “she boasted of her father’s

peculiarities and found in them an excuse for her own oddities”.[3]

Legge continues, saying:

“She had not been among the

Parisians many months ere the more prudish discovered that they had among the

reputed grandes dames an Ambassadress

who did not scruple to behave, and not infrequently, like a grisette. She kissed Count Beust… at an

official reception at the Tuileries, to wheedle him into giving a fancy-dress

ball, and said impertinent things of the Empress who had impulsively taken the

eccentric Hungarian to her heart… I can give only an inkling of her

eccentricities, which were passed over by the Empress with a smile… It would

not have surprised anyone in the monde,

demimonde, or quart de monde to

have seen the Austrian Ambassadress jump on the table and dance the “can-can!”

She was quite equal to it.”[4]

Metternich

was known for her intelligence and wit, and maintained a close friendship with

the Empress Eugenie. The pages of another volume of her memoirs, My Years in Paris (1922), are full of

loving descriptions of the Empress, painting her as a kind and devoted friend. When

the Second Empire fell, it was Metternich whom the Empress trusted to smuggle

her jewels out of the country.[5]

Franz

Xaver Winterhalter, Princess Pauline de

Metternich, 1860. Location unknown

Metternich

was not known as a great beauty. Legge describes her as “slim” and “wiry”,[6]

and in My Years in Paris Metternich

often describes herself as “thin as a lath”.[7]

Yet she became one of the most important fashion figures during the Second

Empire, often referring to herself as “la

singe a la mode”—the fashionable monkey.[8]

She is credited with launching the career of Charles Frederick Worth, and

devotes an entire chapter of My Years in

Paris to describing the great couturier. She writes that “a conversation

with him amounted to a real pleasure. He had a rare insight into women—an

unerring instinct where they were concerned”.[9]

At first wary of an English dressmaker, Metternich was impressed by his fashion

sketches and commissioned two dresses, one of which was worn to a ball at the Salle des Marechaux at the Tuileries.[10]

She describes the sumptuous luxury of the gown:

“I wore my Worth dress, and can

say with truth that I have never seen a more beautiful gown, or one that fitted

me more beautifully. It was made of white tulle strewn with tiny silver discs

(a fashion which, just then, was at its height), and trimmed with crimson-hearted

daises that nestled among little tufts of feathery grass; these flowers were

all veiled in tulle. A broad white satin sash was folded round my waist. I wore

all my diamonds, and—Worth scored his fist success.”[11]

[1] Metternich, The Days That Are No More, 80

[2] Metternich, My Years in Paris, 7.

[3] Metternich, The Days That Are No More, 8.

[4] Metternich, The Days That Are No More, 9-11.

[5] Metternich, My Years in Paris, 199.

[6] Metternich, The Days That Are No More, 34.

[7] Metternich, My Years in Paris, 23, 220.

[8] Metternich, The Days That Are No More, 11.

[9] Metternich, My Years in Paris, 60.

[10] Metternich, My Years in Paris, 56-58.

[11] Metternich, My Years in Paris, 58.

1 comments