All the cool kids are following The Fashion Historian on twitter, @PastFashion.

Charles Frederick Worth (1825-1895) is widely considered the first couturier. My most popular blog post in history is about him, and can be found here. After Worth's death in 1895, his descendents continued the fashion house, until it was closed in 1952 after the death of his great-grandson. But in 2010, the House of Worth returned to the couture stage. The revival is done through the House of Worth Ltd, a new company created by Dilesh Mehta and Martin McCarthy. The head designer is Giovanni Bedin, a graduate of the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne, who has previously worked with Karl Lagerfeld and Thierry Mugler. "We're taking baby steps because Worth is a huge brand with a big heritage and it's brand new again and we have to tell this beautiful story and make people know again the heritage," said Bedin on his rather daunting task of reviving the great couture legend.

House of Worth, Spring/Summer 2011 Couture

My favorite so far is the Spring/Summer 2011 couture collection, which is particularly interesting from an historians perspective. The collection is called Night and Day, and was inspired by an original 19th century Worth dress, which embodied both night and day. “When I saw this dress – the Night and Day dress – it was like a revelation. It's cut in two – one side for day and the other for night with all of the elements like the sun, the moon, bees, flowers, a bat. It was so modern,” said Bedin.

House of Worth, Spring/Summer 2011 Couture

Another obvious inspiration is the tutu, the famous garment worn by ballet dancers the world over. Says Bedin on the tutus: “The tutus – I like the idea that women in the 19th Century didn’t wear mini skirts but the basque was very important and I like the idea of wearing the volume but reducing the length.” His creations certainly capture the opulence of 19th century Worth designs while bringing in a more modern concept of short skirts for women. But is it really that modern?

House of Worth, Spring/Summer 2011 Couture

Well if you wanted to be technical about it, the tutu did develop during the 19th century which most historians categorize as the modern period. The birth of the tutu is quite mysterious, but its first famous appearance was in 1832 in the ballet Les Sylphide, and was designed by Eugène Lami (however no renderings for the tutu remain). It was worn by celebrated ballerina Marie Taglioni, who starred in the ballet as a sylph- an otherworldy spirit who inhabited the air. Soon the tutu became the standard for ballerinas everywhere, its light and floaty qualities emphasizing the ethereal beauty and lightness of the dancers. As the century progressed, the tutu began to get shorter and stiffer, and by the 20th century became the pancake shaped tutu we know today.

Carlotta Grisi in Giselle by J. Brandard, c. 1841. Collection of Marie Rambert.

The history of the tutu is fascinating (and hopefully a lengthy article I have written on the subject will soon be published!) because of the dichotomy of its symbolism. On the one hand it transformed ballerinas into graceful, beautiful creatures, floating about the stage as fairies and princesses, the delicate fabrics and sparkly decorations of the tutu adding to the magic. But on the other hand, the tutu revealed the legs of women in a period when showing legs was a social taboo. It subsequently became an extremely controversial garment. Furthermore, the fairies and princesses of the stage were mostly low class girls in reality. While the famous prima ballerinas enjoyed a celebrity lifestyle, the majority of dancers were simply ballet girls, poor and transformed into sexual objects. The soliciting of sexual relationships with ballet girls was practically institutionalized. At the Paris Opera, rich and influential gentlemen known as abonnés could gain access to the backstage rehearsal hall, where they could flirt with the dancers. While not all ballet girls prostituted themselves, many did and the reputation of the ballet girl as a sexual object was widespread.

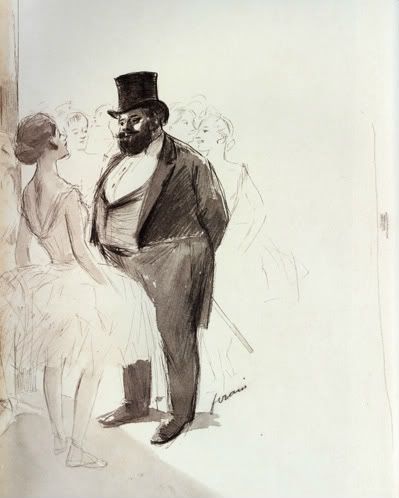

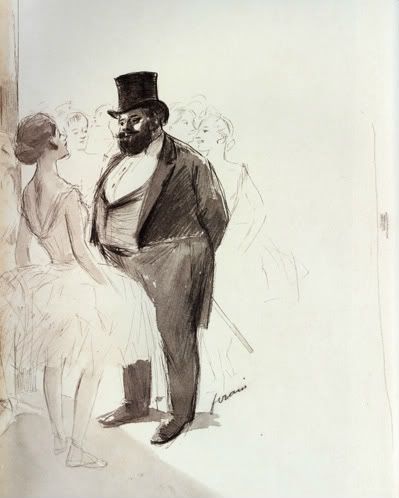

In The Wings No. 3, by Jean-Louis Forain, shows a rotund abonné flirting with a dancer. In the collection of the Boston Public Library.

So what does all this have to do with the beautiful couture creations of Bedin? The tutu was always beautiful, but it was also once a symbol of sexuality and immorality, only donned by the lowest class of women. It is true that ballerinas today have risen far above this heritage, but I think it's interesting to look at these couture tutus in the context of their inspiration- the 19th century. What was once a marker of a lower status has now become a marker of the highest status- the woman able to afford couture. The thought of the House of Worth designing tutus to be purchased by the wealthy and (hopefully) put on display in museums someday would have been absurd in the 19th century. Now it is perfectly normal. And furthermore, in featuring tutus as couture Bedin has taken them off the stage and put them into the "real world", they no longer belong in the realm of costumes but in fashion itself (not that costumes are not a part of fashion, but I think you know what I mean). This is a garment that has made quite a journey!!

Charles Frederick Worth (1825-1895) is widely considered the first couturier. My most popular blog post in history is about him, and can be found here. After Worth's death in 1895, his descendents continued the fashion house, until it was closed in 1952 after the death of his great-grandson. But in 2010, the House of Worth returned to the couture stage. The revival is done through the House of Worth Ltd, a new company created by Dilesh Mehta and Martin McCarthy. The head designer is Giovanni Bedin, a graduate of the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne, who has previously worked with Karl Lagerfeld and Thierry Mugler. "We're taking baby steps because Worth is a huge brand with a big heritage and it's brand new again and we have to tell this beautiful story and make people know again the heritage," said Bedin on his rather daunting task of reviving the great couture legend.

House of Worth, Spring/Summer 2011 Couture

My favorite so far is the Spring/Summer 2011 couture collection, which is particularly interesting from an historians perspective. The collection is called Night and Day, and was inspired by an original 19th century Worth dress, which embodied both night and day. “When I saw this dress – the Night and Day dress – it was like a revelation. It's cut in two – one side for day and the other for night with all of the elements like the sun, the moon, bees, flowers, a bat. It was so modern,” said Bedin.

House of Worth, Spring/Summer 2011 Couture

Another obvious inspiration is the tutu, the famous garment worn by ballet dancers the world over. Says Bedin on the tutus: “The tutus – I like the idea that women in the 19th Century didn’t wear mini skirts but the basque was very important and I like the idea of wearing the volume but reducing the length.” His creations certainly capture the opulence of 19th century Worth designs while bringing in a more modern concept of short skirts for women. But is it really that modern?

House of Worth, Spring/Summer 2011 Couture

Well if you wanted to be technical about it, the tutu did develop during the 19th century which most historians categorize as the modern period. The birth of the tutu is quite mysterious, but its first famous appearance was in 1832 in the ballet Les Sylphide, and was designed by Eugène Lami (however no renderings for the tutu remain). It was worn by celebrated ballerina Marie Taglioni, who starred in the ballet as a sylph- an otherworldy spirit who inhabited the air. Soon the tutu became the standard for ballerinas everywhere, its light and floaty qualities emphasizing the ethereal beauty and lightness of the dancers. As the century progressed, the tutu began to get shorter and stiffer, and by the 20th century became the pancake shaped tutu we know today.

Carlotta Grisi in Giselle by J. Brandard, c. 1841. Collection of Marie Rambert.

The history of the tutu is fascinating (and hopefully a lengthy article I have written on the subject will soon be published!) because of the dichotomy of its symbolism. On the one hand it transformed ballerinas into graceful, beautiful creatures, floating about the stage as fairies and princesses, the delicate fabrics and sparkly decorations of the tutu adding to the magic. But on the other hand, the tutu revealed the legs of women in a period when showing legs was a social taboo. It subsequently became an extremely controversial garment. Furthermore, the fairies and princesses of the stage were mostly low class girls in reality. While the famous prima ballerinas enjoyed a celebrity lifestyle, the majority of dancers were simply ballet girls, poor and transformed into sexual objects. The soliciting of sexual relationships with ballet girls was practically institutionalized. At the Paris Opera, rich and influential gentlemen known as abonnés could gain access to the backstage rehearsal hall, where they could flirt with the dancers. While not all ballet girls prostituted themselves, many did and the reputation of the ballet girl as a sexual object was widespread.

In The Wings No. 3, by Jean-Louis Forain, shows a rotund abonné flirting with a dancer. In the collection of the Boston Public Library.

So what does all this have to do with the beautiful couture creations of Bedin? The tutu was always beautiful, but it was also once a symbol of sexuality and immorality, only donned by the lowest class of women. It is true that ballerinas today have risen far above this heritage, but I think it's interesting to look at these couture tutus in the context of their inspiration- the 19th century. What was once a marker of a lower status has now become a marker of the highest status- the woman able to afford couture. The thought of the House of Worth designing tutus to be purchased by the wealthy and (hopefully) put on display in museums someday would have been absurd in the 19th century. Now it is perfectly normal. And furthermore, in featuring tutus as couture Bedin has taken them off the stage and put them into the "real world", they no longer belong in the realm of costumes but in fashion itself (not that costumes are not a part of fashion, but I think you know what I mean). This is a garment that has made quite a journey!!