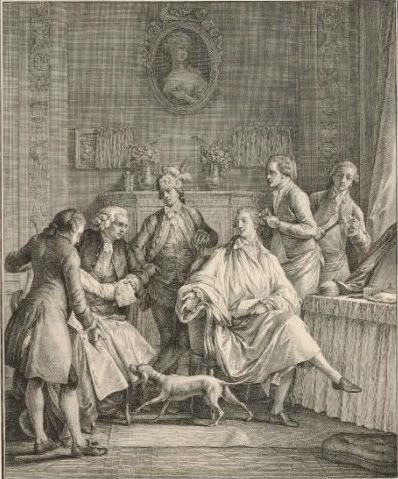

From the Monument du Costume Physique et Moral de la fin du Dix-huitième siècle, 1789

For most, the most intimate portion of the toilette was performed in private, as it's rather difficult to look glamorous when you first wake up. After privately putting on the most intimate garments and getting your hair and face to look presentable, although casual, it was time to present yourself to your visitors. Fashion historian Aileen Ribeiro describes the process:

“On awakening, the fashionable lady rang for her maid who handed her a lace-trimmed manteau de lit for her early ablutions, after which she was dressed in a negligee du matin, a loose robe worn over chemise and stays. Then she was ready to receive visitors in her cabinet de toilette; these could include men, and very often abbes, who acted the part of cicisbei and were always there with the latest news and gossip. It was then that her hair was done, either by a personal maid or a male hairdresser, and the finishing touches applied to the face… The light-hearted intimacy of the lingering toilette was an essential part of dressing in the eighteenth century."

Ribeiro also notes the intimacy of the ceremony, with the lady getting dressed lingering on the undergarments, giving an almost sexual experience. Men also had a morning toilette, using the time to discuss business affairs rather than social ones.

From the Monument du Costume Physique et Moral de la fin du Dix-huitième siècle, 1789

The toilette is often called a ritual, bringing a religious connotation to the event and subsequently showing the importance of fashion in society. The very act of dressing itself is not just a simple daily task, but an important, ‘religious’ experience, showing the status clothing took in eighteenth century society. Clothing was not merely something to cover the body, but to express position and quality. By ritualizing the activity of dressing, each layer takes on an importance, not simply the outermost layer, showing that fashion was not only what was seen but what was unseen. Furthermore, ritualizing the act of dressing makes fashion a performance. A morning dressing ritual shows the elegance and wealth in each layer, not just the ones that will be seen, an important consideration for a culture obsessed with showing off wealth and power. While the toilette started with the French monarchy, in becoming a ritual for the rest of society, the non-royals could emulate the power and style of the monarchy.

A perhaps unintended consequence of turning dressing into a performance is dressing then becomes playing a part. Just as a theater performance is false reality, a woman dressing is emulating a false reality of herself. On the one hand, this performance she is beginning could be an act of submission. As viewers watch her body on display, with each layer she becomes the woman society wants her to be— beautiful, accomplished in the arts, and most importantly a dutiful daughter, wife, and mother. On the other hand, this performance could be an act of rebellion. While society wants to mold the woman into one ideal, with each layer she makes herself into who she wants to be and takes control of herself. The Petit Dictionnaire de la Cour wrote in 1788 that "a charming woman uses more subtlety and politics in her dressing than there are in all the governments of Europe."

The Toilette from William Hogarth's Marriage a la Mode series, 1743-1745.

A similar dichotomy can be seen with men, with the act of dressing either turning a man into a dutiful son or respectable patriarch, or expressing his personal fashion taste which may have been in rebellion to his family or societies' expectations (for example, many young Englishmen, returning from a Grand Tour of continental Europe, would dress in a flamboyant French style, much to the disapproval of the more subdued English view on fashion). It may be argued that taking control of ones identity was far less important for a man, as he already had greater personal autonomy in society. But it may also be argued that men too were under pressure to fit into a certain mold- father sons, run estates, be active in politics, etc- when their desire may have been for another path in life. Society wanted Louis XVI to be a great and gallant monarch like his predecessors, while the man himself was quiet and shy and had no taste for the court ceremonies he nonetheless was forced to participate in (his wife, on the other hand, bucked tradition entirely which greatly contributed to her downfall, but that's for another post).