"For a dress to survive from one era to the next, it must be marked with an extreme purity." ~ Madame Grès

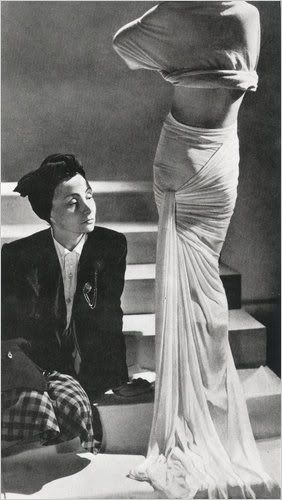

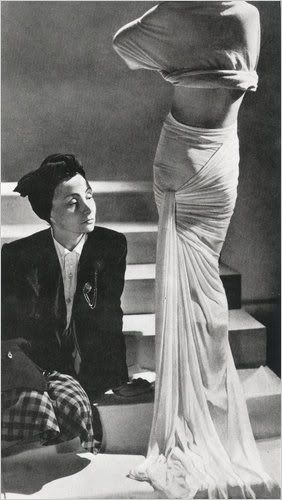

Madame Grès c. 1946.

Photo Credits: Eugene Rubin/ FNAC/Centre national des arts plastiques, Paris

Madame Grès (1903-1993) was a remarkable couturier in the 20th century, known for using delicate pleats which turned ordinary fabric into Greek sculpture.

On display at the Musée Bourdelle in Paris.

Grès was born Germaine Krebs in Paris in 1903. She originally wanted to be a sculptor, but was unsuccessful. She then ventured into millinery, changing her name to Alix Barton. Her design house would be known as Alix from 1934 through 1942. She first gained attention by designing the costumes for Jean Giraudoux's play The Trojan War Will Not Take Place, and quickly became a leading designer of the day, whose clients included everything from duchesses to movie stars (Grace Kelly, Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich are a few of her more famous clients). In 1942 she created the name Grès, a partial anagram of the first name of her husband at the time, Serge Czerefkov. The New York Times called her couture house "the most intellectual place in Europe to buy clothes".

On display at the Musée Bourdelle in Paris.

“I wanted to be a sculptor. For me, it’s the same thing to work the fabric or the stone” Grès once said. And it is a truth universally acknowledged that Grès was indeed a true sculptor of fabric. Her favorite fabric was silk jersey, and a single dress could take from 13 to 21 meters. Her talent for pleating could reduce 9 feet of fabric into a mere 2.8 inches. The drapery of her gowns also showed her technical virtuosity. Long swags of continuous strips of fabric would be incorporated into the front and back of a gown, giving her work a sense of classical antiquity. She also introduced the idea of cutouts, creating little windows in her gowns which revealed the back or shoulder. Wearers of her gowns have said that they felt perfectly secure in her gowns, so impeccable was the construction.

On display at the Musée Bourdelle in Paris.

While Grès is most known for her draped Grecianesque gowns, she also showed talent in less formal designs. Her every day wear showed the same attention to detail and impeccable tailoring that her gowns did.

On display at the Musée Bourdelle in Paris.

Grès had an extraordinarily long career, working until the late 1980s. Throughout this period, which encompassed huge changes in fashion, her work remained consistent and timeless. "Once one has found something of a personal and unique character, its execution must be exploited and pursued without stopping," she said. Her work remains timeless, any one of her elegant gowns could be seen walking a red carpet today. It is easy to see the "extreme purity" Grès would strive for in her work.

On display at the Musée Bourdelle in Paris.

Madame Grès c. 1946.

Photo Credits: Eugene Rubin/ FNAC/Centre national des arts plastiques, Paris

Madame Grès (1903-1993) was a remarkable couturier in the 20th century, known for using delicate pleats which turned ordinary fabric into Greek sculpture.

On display at the Musée Bourdelle in Paris.

Grès was born Germaine Krebs in Paris in 1903. She originally wanted to be a sculptor, but was unsuccessful. She then ventured into millinery, changing her name to Alix Barton. Her design house would be known as Alix from 1934 through 1942. She first gained attention by designing the costumes for Jean Giraudoux's play The Trojan War Will Not Take Place, and quickly became a leading designer of the day, whose clients included everything from duchesses to movie stars (Grace Kelly, Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich are a few of her more famous clients). In 1942 she created the name Grès, a partial anagram of the first name of her husband at the time, Serge Czerefkov. The New York Times called her couture house "the most intellectual place in Europe to buy clothes".

On display at the Musée Bourdelle in Paris.

“I wanted to be a sculptor. For me, it’s the same thing to work the fabric or the stone” Grès once said. And it is a truth universally acknowledged that Grès was indeed a true sculptor of fabric. Her favorite fabric was silk jersey, and a single dress could take from 13 to 21 meters. Her talent for pleating could reduce 9 feet of fabric into a mere 2.8 inches. The drapery of her gowns also showed her technical virtuosity. Long swags of continuous strips of fabric would be incorporated into the front and back of a gown, giving her work a sense of classical antiquity. She also introduced the idea of cutouts, creating little windows in her gowns which revealed the back or shoulder. Wearers of her gowns have said that they felt perfectly secure in her gowns, so impeccable was the construction.

On display at the Musée Bourdelle in Paris.

While Grès is most known for her draped Grecianesque gowns, she also showed talent in less formal designs. Her every day wear showed the same attention to detail and impeccable tailoring that her gowns did.

On display at the Musée Bourdelle in Paris.

Grès had an extraordinarily long career, working until the late 1980s. Throughout this period, which encompassed huge changes in fashion, her work remained consistent and timeless. "Once one has found something of a personal and unique character, its execution must be exploited and pursued without stopping," she said. Her work remains timeless, any one of her elegant gowns could be seen walking a red carpet today. It is easy to see the "extreme purity" Grès would strive for in her work.

On display at the Musée Bourdelle in Paris.